Graphene: Discover the material that could revolutionise technology

Credit: Newsweek

Graphene is impossibly strong, incredibly flexible and good for the environment. We asked a 2D scientist about whether it could change mankind forever.

Think of a material that’s a hundred times stronger than steel but easy enough to bend into a bracelet around your wrist. Imagine that it’s light, conducts heat and is completely two-dimensional: no, not just thin, but literally consisting of a single atom’s thickness.

Such a material seems so good to be true, that even science fiction steers clear of it, for fear of it not being realistic enough.

Graphene, however, is real.

This is a 21st Century material that somehow ticks every box possible for modern life: as durable as diamond, yet flexible and conducive for our insatiable appetite for electricity. So why aren’t we melding super smartphones from this technology? Surely graphene could end the housing crisis, make IoT devices last longer and eradicate batteries as we know it? Could we really build an elevator to the moon from the material found in the core of a pencil?

Right now, graphene poses more questions than it actually answers; a lot of these questions, naturally, are fanciful imaginations of how we can supercharge the human race. We picture our world in 50 years’ time to be made of glass, metal and silicon, yet this material could re-imagine how we build our future.

Where did graphene come from?

This material has only been around for 15 years. Humanity spent centuries, after all, working out how to best harness iron, fire and steel. It’s understandable that the discovery of a brand new kind of substance doesn’t immediately lead to its implementation within months. However, it’s easy to get excited about graphene; to get ahead of ourselves and imagine real cities in the vein of Black Panther’s Wakanda. Just the discovery of graphene sent shockwaves through the scientific community.

“This discovery has subsequently given rise to a whole new scientific discipline – two-dimensional materials science – that looks to explore, understand and exploit graphene and its related materials,” says Dr Nicky Savjani, a 2D Materials Scientist currently working within a multidisciplinary collaboration between The University of Manchester and ESR Technology in Warrington. Dr Savjani works with two-dimensional nanomaterials like graphene and has a PhD in organogold chemistry.

“Graphene is easiest to imagine as a honeycomb sheet of carbon atoms that is completely flat,” explains Dr Savjani. “Although its existence was theorised for over 50 years prior, graphene was first isolated in 2004 by Professors Andre Geim and Kostya Novoselov at the University of Manchester. They discovered that by simply peeling away layers of a graphite crystal, [they found] a material with properties and features never seen before.”

The material found was graphene. Geim and Novoselov were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2010 for their discovery, which opened up the doors to more research, more funding and more interest in the material. Dr Nicky Savjani is just one of the thousands of scientists working on 2D materials, thanks to this discovery.

“There are numerous ‘growing pains’ in expanding the production and application of the material to the consumer marketplace,” says Dr Savjani. “The science of graphene is still in its infancy; we are still learning so much about its fundamental properties. But the scientific community are discovering new insights into the material at staggering rates.”

IoT is taking over the world. It won’t be soon before smart homes are commonplace: refrigerators and lightbulbs connected to the internet are merely the first waves of a technological tsunami.

The number of IoT devices year on year is multiplying at an astonishing rate. However whilst we originally projected IoT’s growth based on what made sense with the materials we currently have, new materials could throw a spanner in the works, somewhat. Suppose, for example, that batteries can be completely redesigned. If batteries can last longer and fully charge, say a smartphone, in under half an hour, we could see the IoT revolution scale even further, even faster.

“Graphene has already started to be implemented within flagship smartphones,” says Dr Savjani. “Huawei uses graphene as a replacement cooling system, it reportedly conducts heat away fast, keeping the device cool even under heavy loads whilst adding minimal weight. Samsung is developing graphene-modified lithium-ion batteries that are reported to increase charge capacity, as well as decrease charging times to a fifth of current charging technologies; all of this whilst acting as a fire retardant, significantly reducing the known explosion risks of lithium-ion cells.”

Batteries are just one example of how graphene could supercharge IoT. The material could well be integrated across devices, wearables and inventions that we haven’t even seen, yet.

“The applications of graphene beyond phones are exhaustive,” Dr Savjani confirms. “It can be used to improve the sensitivity of touch screens, allowing for gesture control by just simply hovering your finger over the screen. It could also replace existing electronic materials – such as silicon for computer chips, or copper, lead and indium-tin-oxide as conductors – to assist in the ‘miniaturisation’ of electronic architectures of computer chips and other electronic components.”

With electronic architectures getting smaller, the capabilities of computing are improving. Graphene could accelerate this.

“This could help in making the next generation of computers incredibly fast; allowing us to break away from Moore’s law, which currently limits improving computer speeds.”

Graphene could have a variety of IoT benefits

It’s not just batteries and chips that graphene can be used in. This is a multi-functional material that could be used to build the hardware of wearables and IoT devices, not just the software.

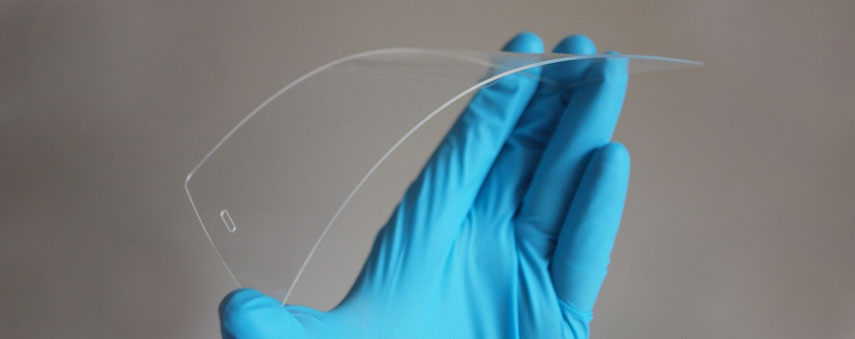

Dr Savjani believes that one of the defining characteristics of graphene – its flexibility – could lead to smartphones themselves being redesigned entirely. “[Graphene] could lead to smartphones that are as thin as paper, can be folded or rolled, integrated within complex surfaces, whilst packing the same performance punch as current smartphones,” he says.

Flexible smartphones’ mass popularity is apparently just around the corner thanks to the likes of Samsung’s Fold design. Phones that are made of a material that folds and bends like paper are a completely different prospect though: should they even be classified as smartphones?

So if we’re no longer bound by a rigid rectangle made of glass on which to communicate, where do we go from here? AR headsets are one innovation that feels more like a “when” rather than an “if”; could we also see a rise in smart clothing and the revolution in wearables?

“Looking further ahead in its development cycle, graphene will contribute to making wearable technology possible,” confirms Dr Savjani. “Evidence has shown that graphene-based electronics and technologies could utilise the materials’ mechanical and electronic properties to produce ultrathin electronics that are flexible, stretchable and wearable.”

Internet speeds could improve with graphene

2020 is set to be the year of 5G. 2019 has seen the foundations of the technology, from television adverts displaying the lightning capability of 5G to Glastonbury Festival offering a demonstration of a 5G phone.

The switchover to fifth-generation cellular technology is expected to change the world, despite concerns from some. More data means faster internet, the ability for bigger downloads and inevitably this could lead to bigger, better content on devices. Wireless internet, however – whether 5G or Wi-Fi – is still limited.

“One of the limiting factors of improving wireless internet speeds comes from the increasing congestion that exists within the mobile spectrum,” says Dr Savjani. “Due to increasing demands of wireless communications, telecommunication companies spend billions on acquiring small slots of the spectrum (between 800 and 2100 MHz) that is sporadically released by the government. For enabling higher speed and wider bandwidth data transmission, it is therefore critical to be able to access and broadcast at an unused part of the spectrum.”

The science of graphene is still in its infancy; we are still learning so much about its fundamental properties. But the scientific community are discovering new insights into the material at staggering rates.

Dr Nicky Savjani

“One promising candidate for wireless communication is to access the Terahertz band (0.1 THz – 10 THz), which could allow for wireless Terabit-per-second (Tbps) links, improving dataflow by up to 1,000-fold.”

Graphene poses alternate questions about the internet’s timeline in the 2020s. We thought that we know the direction that the internet would head in with 5G but graphene could blow all of that wide open.

“The technology that allows us to transmit and receive signals at these frequencies is desperately needed. Current technology can only access a small amount of this spectrum, with severe performance limitations inhibiting its nationwide adoption. Laboratory studies have shown that graphene may be the key component in developing such devices, allowing for miniaturised antennas, waveguides and aerials to be built for Terahertz communication circuits.”

The technology could be huge for medicine and the environment

Is it selfish of us to wonder about smartphones and a less clunky smartwatch as soon as we hear about a new wonder material? Perhaps. We could blame it on the omnipresence of consumerism; it’s natural to relate new information back to a relatable scale, after all.

Graphene is likely to turn your household upside down. Your phone, your watch, kitchen appliances, even the four walls around you could all be infused with the substance in years to come. It’s a huge world out there though and graphene is going to affect that, too.

Graphene could be hugely beneficial for the environment. It could be used to help cut down on carbon emissions and potentially kickstart cleaner energy methods.

Graphene could be equally as impressive in advancing healthcare and medicine. The material has antimicrobial properties which could reduce infections, making it the perfect material to coat medical devices, but also implants. Should brain implants rather like the ones teased by Neuralink become commonplace, it’s likely that graphene could be used.

“Functionalised graphene could be used as an effective cancer-treatment system: [it] could be used as a drug-carrier for targeted delivery of anticancer chemotherapy drugs, or be incorporated within small fluid-devices for the removal of tumour cells in blood,” says Dr Savjani. “Ultrasmall sensors may also allow for on-the-spot diagnoses, without the need for biopsies. In other fields, graphene can be used as the structural platform for in stem cell therapies for numerous neurological and genetic disorders.”

“Ultrathin and light graphene sensors could be developed; [they] allow for the real-time monitoring of any surface of the body, including directly on organs such as the heart. It has also been incorporated within latex condoms to make them thinner, stronger, safer and more flexible than ever before to aid birth control.”

What are we waiting for exactly?

We live in a mad world and even to remind ourselves of that is a cliche. Politically, the stuff of satire has become real. Culturally, we explored almost every avenue we possibly could and now live by the law that even something old is new to someone.

Technologically, things famously advance at ever-increasing rates. Partly to satisfy our insatiable appetite for the new, partly because companies need to edge ahead of the pack and partly because we can.

Consider a kitchen appliance like a refrigerator. Think of how it looked in 1950s American diners and how it looks in 2019. The function of it is identical. There’s been such precious little update to it simply because there has never needed to be any. It’s quite a different tale for the mobile phone, which today looks like a completely different object from its brick-like predecessor.

Technology is a marathon runner that the average person struggles to keep up with. Most of us drop out of the race in our 30s or 40s and simply allow technology to wash over us: something for our kids to enjoy and the IT guy at the office to give us a short demo of so that we don’t break the new printer.

Technology doesn’t need another excuse to run away from us but graphene might provide it. If every aspect of tech becomes infused with this supermaterial, from screens to batteries, the material your phone is made out of to the imminent brain implant in your head, it’s going to be difficult to keep up with.

So where is it all? Graphene promises infinitely-charged products, carbon capture and t-shirts that connect directly to the internet, so why haven’t we seen any of it?

“The science of graphene is still in its infancy; we are still learning so much about its fundamental properties,” Dr Savjani reasons. “But the scientific community are discovering new insights into the material at staggering rates.”

Research isn’t the only reason, however, that graphene isn’t everywhere just yet.

“There are also economic impacts of introducing the new technology: the ability to produce pure, defect-free graphene suitable for use in electronics is currently extremely expensive,” he continues. “But with the rapid rise in the number of graphene producers around the world, supplying superior materials with the costs are rapidly declining, the technology will be available to exploit to all.”

Mass-production of a brand new material is challenging. Dr Savjani expects it to be an expensive process, however, with more and more graphene-incorporate products reaching market, these obstacles are being overcome.

For those who do desperately try to keep up in the race with technology, Dr Savjani says that graphene has been seen as an “overpriced gimmick”. Attitudes are changing now.

“Only now have products begun to show the true potential of graphene as a world-changing material,” he says. “Some researchers believe that graphene will pervade all aspects of the world within the next ten years, others believe it will be 30.”

“But it is only a matter of time before graphene will lead us into the next technological era.”