How real is the threat of killer robots?

In 2015, a 22-year-old man in Kassel, Germany, was grabbed by a robot and crushed to death against a metal plate at a car production plant. The victim was part of a team setting up automated machinery at the plant.

The incident at the plant raised alarm and not just in Germany. With worldwide media in a state of hysteria, a report later revealed that the man killed by the robot had set it to a faster speed. It’s easy though to understand why such an episode would provoke panic.

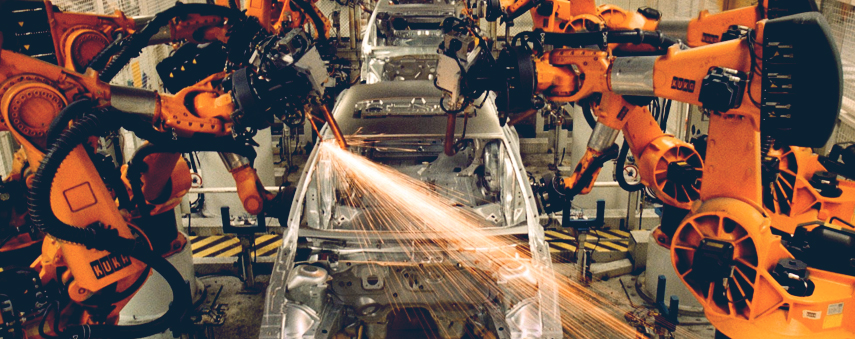

Robotics have been employed by the automotive industry as early as 1961. The idea that robots could one day replace human workers is a very real fear for many; with so many parts and components to be accounted for in the process of building a vehicle, it’s perhaps no surprise that redundancy hits car manufacturers hardest in times of crisis, since disrupting one link of the supply chain can have a massive impact for others. With the risk of job loss seemingly always around the corner, it’s easy to distrust new innovations in the industry.

Robots involved in workplace deaths reaffirm distrust. Many automotive robots are semi-autonomous, using machine vision systems to react to changing environments. In 2018 for example, Kia integrated wearable industrial robots in their assembly lines, giving workers protection, mobility and strength to perform their jobs. The idea of passing such power to machines is worrying for many.

Perhaps the biggest fear is not of becoming subservient to an intelligent race of machines. It’s more that problem-solving machines may not be clever enough.

Do AI robots always protect us?

AI is designed to make decisions on its own. From self-driving cars to spam filters, artificial neural networks are built like our brains. The idea is for them to learn, to analyse data and to process it without our help. But what if it comes to a different conclusion to the one we’d have made?

In 2016, Joshua Brown became the first known fatality of an autonomous vehicle crash. Brown’s Tesla Model S electric sedan collided with a semitrailer truck in Florida. The car was being controlled via autopilot and was set to cruise at 74mph. According to data ascertained after the crash, Brown’s hands were on his steering wheel for just 25 seconds of his final 37-minute journey in his car.

Whilst theorists rumble on about the possibility of killer robots, there is no doubt that the human race is beginning to assign life-or-death decisions to technology.

The truck pulled out of a side road and onto the highway. Brown’s Tesla passed underneath the trailer, as it didn’t have sideguards. The car’s airbags were reportedly deployed after hitting trees off the road, rather than when the vehicle smashed into the truck.

The news sent shockwaves through the technology community. No machine is faultless and this Tesla incident suggested that relying on the car’s own decision-making was dangerous. Earlier on this year, tests run by Consumer Reports found that Tesla’s lane-changing navigation reacted worse than human drivers when trying to change lanes automatically.

Leaving your life in the hands of Elon Musk’s motor business spells fear for many. The car manufacturer released a statement in the wake of the lane-changing report, arguing that it is “a driver’s responsibility” to remain in control of a Tesla vehicle at all times, including when executing lane changes.

The fatality in Florida suggested a similar hypothesis. According to data from Joshua Brown’s final Tesla trip, the brake was never applied by the driver. The car issued six warning alerts for Brown to apply his hands to the wheel of his vehicle during the trip.

Robots vs. humans: who’s usually to blame?

When robots are involved, a thread runs through fatality cases. An investigation into the car plant incident attributed the event to “human error”. A similar case happened in Japan in 1981, when Kawasaki engineer Kenji Urada was fatally pushed into a grinding machine by a broken robot he had failed to switch off completely.

Incidents where robots supposedly turn on people are almost always blamed on the user. Unsurprisingly, there has never been a clear case of AI choosing to destroy its masters. However, whilst theorists rumble on about the possibility of killer robots – what if the government have covered up incidents? – there is no doubt that the human race is beginning to assign life-or-death decisions to technology.

Driverless vehicles still require human oversight. One day, however, they may not, and we could be at the mercy of our AI chauffeurs. In car factories, humans are warned against entering the cages that the robots operate in. Workers are well aware of the dangers of these machines and their abilities to backfire, treating them in a similar manner to how a zoologist would with a captive animal. In the military, autonomous weapons may yet be inevitable. Will predator drones replace their human pilots with artificial intelligence? Will a programmed computer decide where a bomb should be dropped?

As always, it’s human interaction that lies at the centre of the debate. AI robots are by themselves, not inherently evil. It’s up to our species to treat their advancement with caution and be aware of their limitations, as much as their staggering ability to transform our lives.